Capturing sound changed everything about how we connect to the past. Before that, sound existed only in the moment. Once spoken, it vanished. That’s why the first sound ever recorded holds so much meaning. It’s more than a technical feat. It’s the beginning of remembering voices from the past. So, what was the first sound ever recorded, and why does it matter? To answer this, we need to go back over 160 years.

Jump to:

The First Sound Recording and Its Inventor

The first sound ever recorded was a short clip of a French folk song in 1860. It captured the tune “Au Clair de la Lune,” sung by an unknown voice. This wasn’t just a scratch on paper. It was a voice frozen in time. For over a century, no one could hear it. Then in 2008, audio experts brought it to life using modern tools.

So, who invented the first sound recording device? That honor goes to Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville. He was a Parisian typesetter, not a scientist. But he created the phonautograph in 1857. His goal wasn’t to play background sound. He only wanted to see what it looked like. His machine drew sound waves on blackened paper using a stylus and horn. The idea was visual, not musical. But unknowingly, he became the first person to record sound decades before playback was possible.

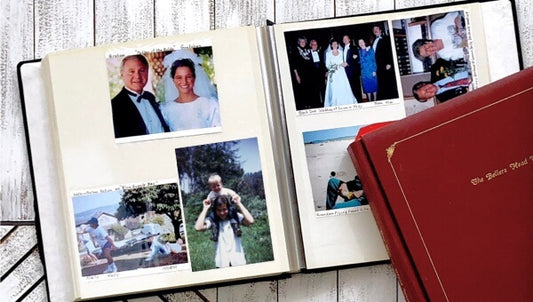

Scott’s forgotten breakthrough paved the way for the technology we rely on today to save our most personal recordings. Whether it’s early sound experiments or cherished family moments, the desire to preserve what matters still drives us. It’s the same reason people now convert DVD to digital - to keep memories alive, accessible, and safe for the future.

How The Phonautograph Worked

The phonautograph captured sound using a simple stylus, horn, and smoked paper. When someone spoke or sang into the horn, the vibrations moved the stylus. That stylus scratched the sound waves onto soot-covered paper. It looked like a line graph, not a record. No one could play it back at the time.

Scott’s machine wasn’t a player. It was a recorder only. The idea of replaying sound hadn’t happened yet. But his invention gave science a tool to study sound. Researchers could look at wave patterns and better understand pitch, volume, and speech.

Even though the phonautograph couldn’t produce sound, it was the first device to capture its shape, laying the groundwork for modern techniques that use visual signals to decode and restore old recordings, just like we do today when we convert Video8 or DVD to digital.

Rediscovery And Modern Playback

In 2008, the first sound ever recorded was finally heard thanks to digital tools. Audio historians from the First Sounds project worked with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. They scanned Scott’s paper using high-resolution cameras. Then, they used software to turn the grooves into sound waves.

The result was haunting. A fragile voice from 1860, slightly distorted, sang a simple folk tune. It wasn’t perfect, but it was real. For the first time, we could hear someone sing from an era before telephones, radios, or records. That brief recording reshaped how we view early sound technology - it proved that even the most fragile formats can be revived.

Projects like this remind us why it’s important to preserve our own family history. Just as Scott’s forgotten recording was brought back to life, we now have the tools to transfer 8mm film to digital and protect our memories before they fade away.

Edison’s Phonograph vs. the Phonautograph

Thomas Edison’s phonograph, introduced in 1877, was the first machine that could both record and play back sound. It used tinfoil, a stylus, and a diaphragm to capture and reproduce audio - unlike Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville’s phonautograph from 1857, which only traced sound waves on soot-covered paper.

Edison’s invention had immediate, practical value, allowing people to hear music and messages. Because it could be heard, his recording was long considered the first—while Scott’s silent traces were forgotten until researchers revived them with modern tools.

Key differences

Phonautograph (1857):

- Visual recording only

- No playback

Phonograph (1877):

- Recorded and played back audio

- Usable for communication and entertainment

Scott captured sound before it could be heard. Edison made it audible. Together, their inventions paved the way for today’s preservation tools - including the ability to transfer VHS to digital and keep voices from the past alive.

Why The First Recorded Voice Matters Today

The first sound ever recorded changed how we remember people, music, and culture. It wasn’t about the song itself. It was about preserving a human moment. That one clip from 1860 showed that sound could last forever if captured right.

From a science angle, it sparked a new field of study. Audio preservation became a real goal. Museums, libraries, and labs now save everything from speeches to street sounds.

Here’s why the first sound still matters:

- It showed sound can be recorded and preserved, just like writing or photography

- It helped launch the field of audio archiving

- It gave museums a reason to collect and digitize historical sound

- It inspired new tools that help families save personal memories

- It proved that voices, even from 160 years ago, can still be heard

How One Forgotten Recording Changed Everything

The first sound ever recorded was more than a scratch on paper. It was the start of audio history. It changed how we think about memory and voice. Without Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville and his phonautograph, the idea of recorded sound may have come later. Now we know his work was first. From 1860 to now, that single moment echoes forward.

At Capture, we honor that legacy by helping families preserve their own meaningful recordings. Whether it's home movies, old tapes, or cherished voices, every memory deserves to be heard - not lost. Convert your personal videos to digital today and protect them for generations to come.